As we honor the legacy of Martin Luther King Jr. today, let's delve into a lesser-known yet impactful chapter of his story, and the power of comics.

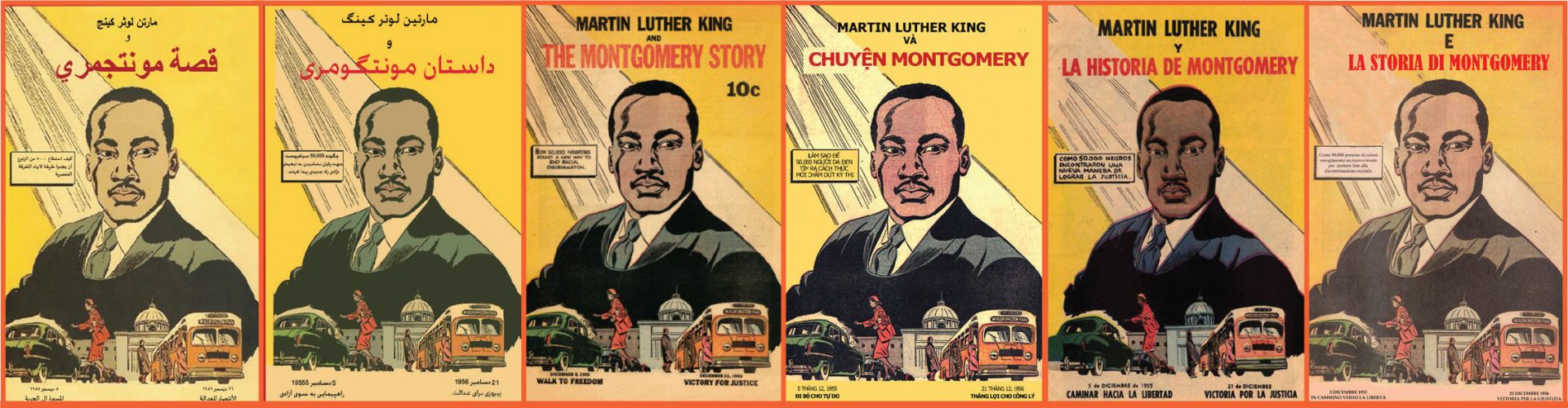

The "Martin Luther King and the Montgomery Story" comic Published in 1957 by the Fellowship of Reconciliation, was a 16-page story that served as a visual chronicle of the Montgomery bus boycott, featuring the iconic figures of Martin Luther King Jr. and Rosa Parks.

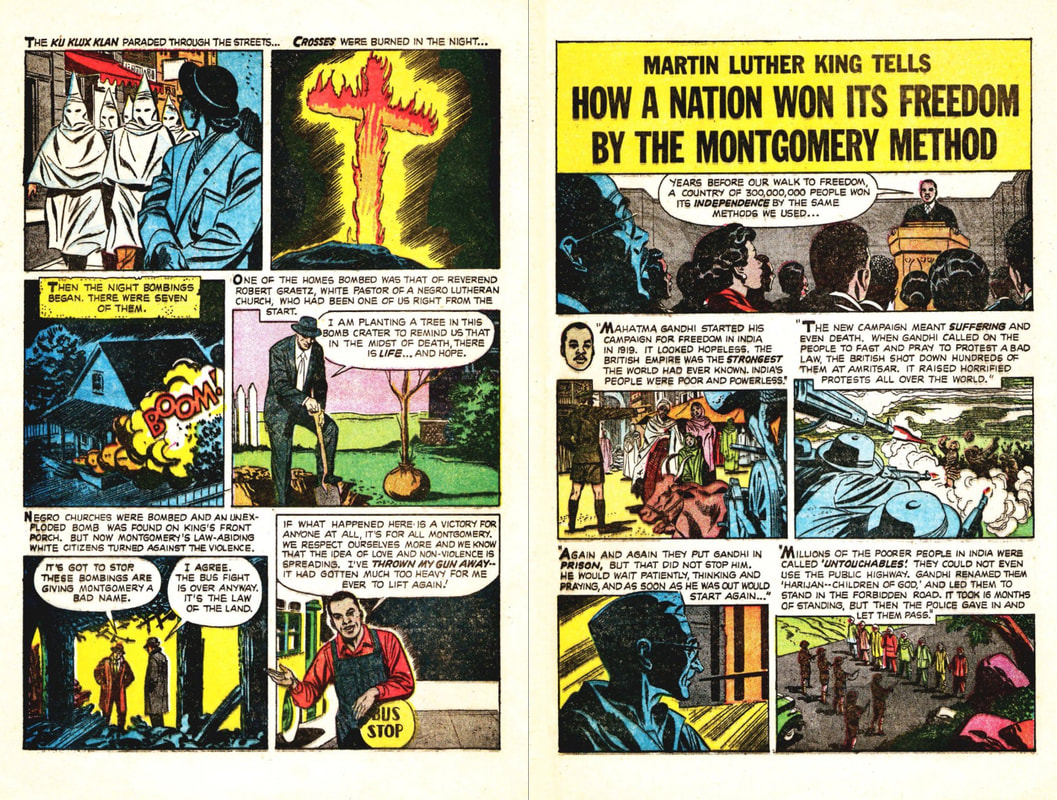

Beyond its historical significance, the comic advocates for the principles of nonviolence, and providing a lesson on the art of nonviolent resistance. In years past we've shared this comic on our facebook page, but this year I wanted to explore the book more and how, once again, comics were used to help spread the message. Not only did this this comics influence the movements in the South but across the globe, leaving an indelible mark on the fabric of civil rights history.

In the wake of the successful Montgomery bus boycott, an initiative took shape in 1957 by the Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR) executive secretary and director of publications by Alfred Hassler, along with Reverend Glenn E. Smiley, conceived the idea of using to narrate the story to a broader audience. With personal ties to Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Smiley advocated to reach wider demographics, particularly those with lower reading levels by producing a comic book.

Securing a $5,000 grant from the Fund for the Republic, the group, endorsed by Dr. King himself, hired cartoonist Al Capp who generously produced "Martin Luther King and the Montgomery Story" at no cost. Co-authored by Hassler and Benton Resnik, and illustrated by Sy Barry, the comic was published in December 1957, printing 250,000 copies, and marked a significant contribution to spreading the message of the bus boycott.

In a departure from the conventional channels for comic distribution common during that time —newsstands, pharmacies, and candy stores—The Montgomery Story took a distinctive path. The FOR disseminated the comic among civil rights groups, churches, and schools and locations found in the Green Book.

The Green Book, established by NYC mailman Victor Hugo Green, was an annual guidebook for African-American roadtrippers from 1936 to 1967, initially focusing on New York and later expanding to cover much of North America. Termed "the bible of black travel" during the Jim Crow era, helped African-American travelers locate friendly lodgings, businesses, and gas stations in a time of legal bias. Despite its crucial role, the guide remained relatively unknown beyond the African-American community and ceased publication after the Civil Rights Act of 1964 rendered its necessity obsolete.

This unconventional strategy extended to promotion in pro-Civil Rights publications like the National Guardian and Peace News. Dedicated FoR staff members, including Jim Lawson and Glenn Smiley, undertook journeys throughout the South, conducting nonviolence workshops and distributing the comic to younger participants as a resource for study. Beyond its original release, FoR later crafted a Spanish version for distribution in Latin America. Surprisingly, the Spanish edition featured a complete drawn by a different artist. Despite an initial print run of 125,000 copies, only a few of the Spanish versions have endured over time.

Martin Luther King and the Montgomery Story left an mark on the civil rights movement, and resonating with activists such as the Greensboro Four. In January 1960, an 18-year-old North Carolina A&T State University student named Ezell Blair encountered "Martin Luther King and the Montgomery Story" in Greensboro, N.C. After reading it, Blair shared the comic with his roommate, Joseph McNeil. Inspired by the comic's message, McNeil made a historic decision, declaring, "Let's have a boycott!" This pivotal moment marked the beginning of a significant chapter in the civil rights movement.In February of the same year, the group, later recognized as the Greensboro Four, initiated a sit-in at the segregated lunch counter of a local Woolworths. Requesting coffee service, they were denied, and in response, they steadfastly refused to leave, making a powerful statement against racial segregation. A protest that had actually happened in St. Louis years before.

The comic reached unexpected corners of the globe through the 2008 American Islamic Congress HAMSA initiative. Thousands of Arabic and Persian versions found their way to democracy advocates in the Middle East. During the Egyptian Revolution of 2011, U.S. Representative John Lewis acknowledged the 50-year-old comic as a catalyst in the protests, emphasizing its role in inspiring collective action.

The comic's impact was seen in the transformative effect it had on Georgia Congressman John Lewis during his teenage years. Lewis, inspired by the philosophy of nonviolence depicted in the comic, became a crucial figure in the Civil Rights Movement. The comic's enduring legacy even shaped Lewis' later collaboration with Andrew Aydin, who recognized the potential of comic book storytelling in conveying impactful narratives of social justice in the book March.

Reflecting on why he thought a comic format was the best way to tell the story of his role in the civil rights movement John Lewis said, "Once he told me about it, and I connected those dots that a comic book had a meaningful impact on the early days of the Civil Rights Movement, and in particular on young people, it just seemed self-evident. If it had happened before, why couldn't it happen again?"

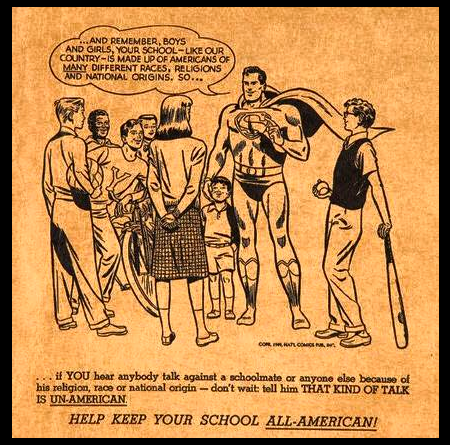

Throughout history, comics have consistently served as a platform for championing social justice by addressing pressing issues such as racism, inequality, and discrimination. From the first issue of Action Comics #1 where a new character called Superman fought slumlords, political corruption and spousal abuse to pioneering works like "The Montgomery Story" and many others comics have demonstrated the enduring power of comics to advocate for change, fostering a sense of empathy and understanding among readers while amplifying the voices of marginalized communities.